Protecting the Congo Peatlands

Developing options to protect the central Congo peatlands and livelihoods of peatland-dependent communities in the Republic of Congo

Professor Simon Lewis, Professor Ifo Suspense Averti, Dr Jonas Ngouhouo-Poufoun, Cassandra Dummett, Lettycia Moundoungas Mavoungou, Eustache Amboulou, Jaufrey Bamvouata.

Executive Summary

Scientists produced the first map of the central Congo peatlands in 2017, revealing it to be the world’s largest tropical peatland complex. The area spans 11.3 million hectares of western Democratic Republic of Congo, and 5.5 million hectares of northern Republic of Congo. The peatlands appear largely intact, are one of Earth’s most carbon dense ecosystems, host globally important wildlife, and support local communities’ livelihoods.

Here, we report on interviews with peatland stakeholders in the Republic of Congo (also known as Congo-Brazzaville), to understand their uses of the peatlands, and their expectations and aspirations for the future of the peatlands. We then survey options to protect the peatlands that are consistent with stakeholders’ expectations for the future.

There is a widespread desire by stakeholders to protect the peatlands from conversion to other land uses and to protect the local and indigenous peoples’ peatland-dependent livelihoods. There is a desire to recognise the current management, given that the peatlands appear to be currently largely intact, and to build on this for the future. There was strong opposition to creating protected areas that stop local communities and Indigenous peoples from accessing the peatlands and continuing with their traditional uses of the peatlands.

The government wants the peatlands to generate income for the government, which it does not at present. The government wants the region to develop sustainably, including maintaining the peatlands. The local communities want to increase their incomes and have access to local health and other services. Both point to the need for a green economy in the region.

We then investigate how peatland and livelihood protection could occur by surveying the options. The recent Republic of Congo Sustainable Management of the Environment Law, passed in late 2023, prohibits industrial development in the peatlands and commits the government to granting a special legal status to the peatlands. This provides a framework for protecting the peatlands.

To meet the expectations of the stakeholders, the government could build on the 2023 Law and pass an implementing decree (an executive order with legally binding consequences) to protect the peatlands and the peatland-dependent livelihoods, by prohibiting changes to the peatlands’ vegetation and hydrology, and formally including the rights of local communities and indigenous peoples to fishing and other sustainable livelihood activities. Before a decree is passed, communities will need to be consulted on the proposed changes, in a process of Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC).

The stakeholders are also in favour of long-term tripartite management of the peatlands, by government, local communities and Indigenous peoples who utilise the peatlands, and expert civil society organisations. This should also be included in an implementing decree.

Given that 5.5 million hectares of peatlands is too large to manage as one area, the region will need to be split into a small number of area-based management units. Deciding on these will need to consider the extent of the peatlands, their hydrology, local community use, existing land use and management, and government administrative boundaries. When considering these management units, decisions are also needed on which legislative framework will be used to demarcate and manage different areas of the peatlands. These include Community Reserves, Other area-based Effective Conservation Measures (OECMs), UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, and others. Each has its advantages and challenges which we discuss.

Having identified the broad consensus on peatland protection and an approach to implement the consensus, we identify preparatory studies needed to support the government in building on the substantial progress in protecting the peatlands included in the 2023 Sustainable Management of the Environment Law: determining the legal extent of the peatlands area, identifying which local communities utilise the peatlands, and defining potential future area-based management units.

In the final part of the report, we outline the options to finance an ambitious plan to formally protect the Republic of Congo’s peatlands, and to empower the local communities and indigenous peoples who currently manage them. We report on the order-of-magnitude costs for each step of the process and multiple realistic sources of funds, suggesting an ambitious plan is feasible.

Peatlands protection is logical investment. If the Republic of Congo peatlands were drained this would add 34 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere over a couple of decades. The damage inflicted on the world’s people, in financial terms, of adding this carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, is $6.4 trillion.

Protecting the peatlands may cost approximately $15 million annually in management costs, with set-up costs of about $100 million. Protecting the peatlands from drainage is therefore a very large avoidance of future damage for a modest near-term investment: the investment avoids the potential for 16,000 times more economic damage than the financial investment itself.

Looking forwards, the funds needed to sustainably manage the peatland over the long-term will require both ingenuity and robust institutions. While challenging, the prize of success is great – the Republic of Congo would be a world leader in rights-based conservation as it protects the world’s most extensive tropical peatland and the unique cultures that depend on it, with globally significant benefits to our climate and biodiversity.

Background

The world’s largest tropical peatland complex is in the central Congo Basin (Dargie et al. 2017). It covers 5.5 million hectares of north-eastern Republic of Congo and 11.3 million hectares in western Democratic Republic of the Congo (Crezee et al., 2022). It is of great importance locally to those that utilise the peatlands; it is of national importance in terms of the provision of clean water; it is of regional importance, cooling the region and generating the rainfall that agriculture relies on; and it is of global importance as a large store of carbon in the peat, some 29 billion tonnes, equivalent to three years of global fossil-fuel emissions and as home to lowland gorillas, forest elephants, and other precious biodiversity (Dargie, 2015; Crezee et al., 2022; Sonwa et al., 2022).

The central Congo Basin peatlands were first mapped and brought to world attention in 2017. This has resulted in national, regional and global interest in protecting the peatlands for the long-term.

The central Congo Basin peatlands were first mapped and brought to world attention in 2017 (Dargie et al., 2017). This has resulted in national, regional and global interest in protecting the peatlands for the long-term. The central Congo Basin peatlands appear largely intact, without the major land-use change that is affecting other tropical peatlands, such as in Southeast Asia which has seen widespread conversion to oil palm, timber and rice production (Dommain et al., 2016; Jenkins et al., 2025). However, forestry, mining, agriculture, oil and gas concessions overlap the peatlands, and could potentially damage them through degradation, drainage and pollution (Dargie et al., 2017; CongoPeat Consortium, 2023). Of critical importance for the many ecosystem services they provide, the peatlands must remain wet (Dargie et al., 2017; Joosten, 2024). Draining the peatland would result in a loss of ecosystem services such as fish for local communities, rapid and high emissions of carbon dioxide due to peatland degradation and accelerating climate change (Dargie et al., 2017; Jenkins et al., 2025).

Protection, conservation, preservation and other terms are words with differing meaning to differing stakeholders, but they are often used almost interchangeably. This can lead to misunderstandings, which can be especially acute when considering natural resources that local community access, and have value globally, for example for carbon and biodiversity. In this report we use the term ‘protection’, and then define what we are protecting, such as customary access or carbon or biodiversity, to be more neutral.

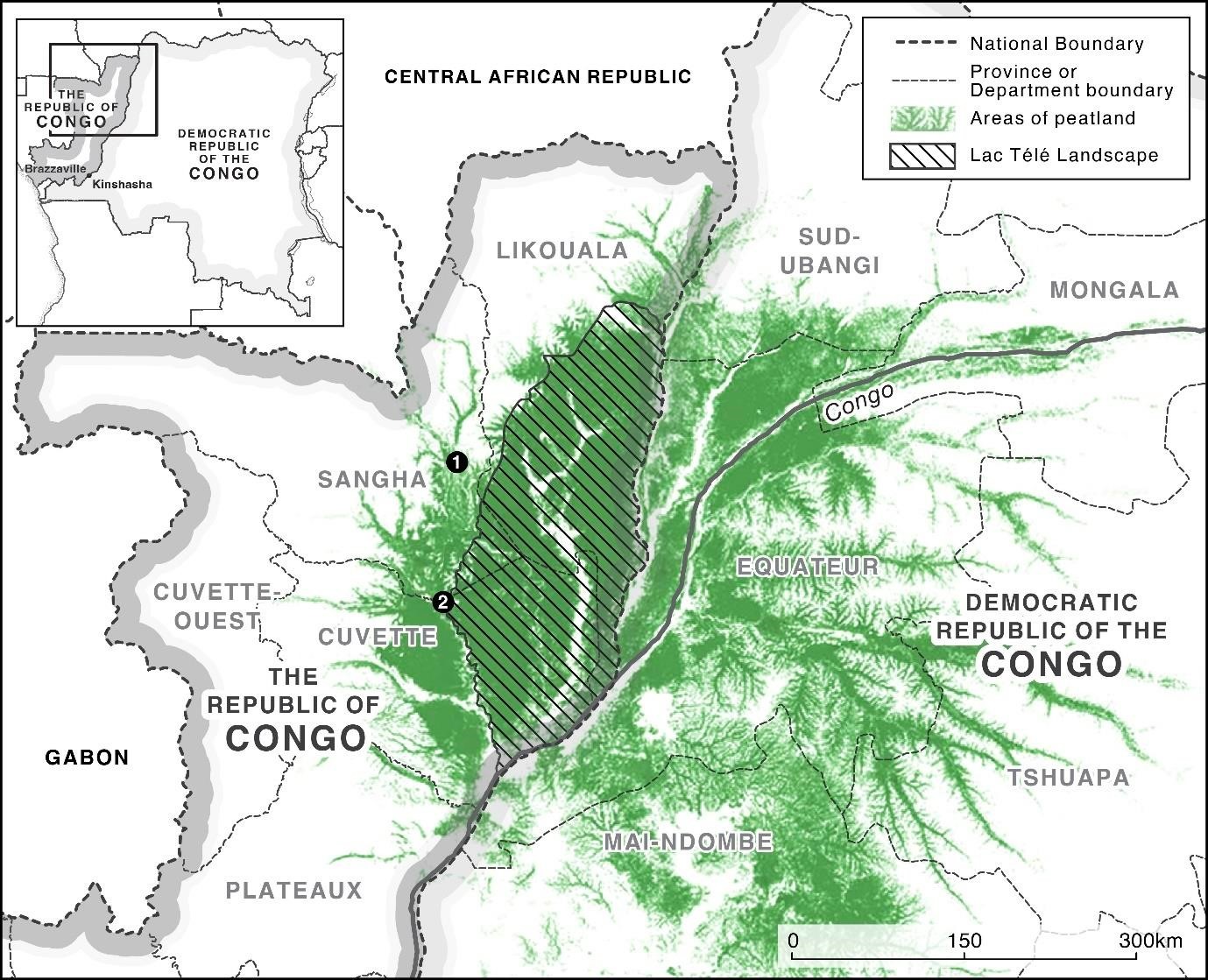

Map of the Republic of Congo showing study sites 1 & 2, the peatlands area (Crezee et al., 2022) and the Lac Télé landscape covering the administrative districts of Bouanila, Dongou, Epena, Impfondo, Liranga, Loukolela, Mossaka, Ntokout and Pikounda (Global Environment Facility, 2021). Map created by Miles Irving, Department of Geography, UCL.

Purpose of the report

Our aim in this report is to provide robust research that contributes to the decision-making process led by the government of the Republic of Congo on the future of the peatland region. We focus on the peatlands of the Republic of Congo only, to assess how the peatlands are currently utilised by local communities, and the benefits that accrue to the government of the Republic of Congo, civil society, and the private sector.

We assess which options to protect the peatlands might be supported by diverse stakeholders in the Republic of Congo and internationally, and suggest a possible pathway forward alongside some practical next steps. Finally, we consider the options for financing long-term protection while supporting peatland-dependent livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The research was conducted jointly by University College London in the UK and Marien Ngouabi University in the Republic of Congo. The research team was Professor Simon Lewis, Professor Ifo Suspense Averti, Dr Jonas Ngouhouo-Poufoun, Cassandra Dummett, Lettycia Moundoungas Mavoungou, Eustache Amboulou, Jaufrey Bamvouata. The research was funded by the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment. The research was conducted between January 2024 and July 2025.

Stakeholder interests in the peatlands

We identified key stakeholders, the benefits the peatlands provide, and expectations and aspirations for the future using a literature review and stakeholder mapping. For the stakeholder mapping we analysed 222 sources of information (87 reports, 81 academic journal articles, 29 websites, briefings, bulletins, direct links, 19 official government documents, 4 books, and 2 academic theses). Between January and November 2024, we conducted online and in-person interviews with 55 stakeholders, summarised below, from the civil society (27), Republic of Congo government (14), international organisations and donors (9), local communities and Indigenous Peoples (3), and the private sector (2), to assess the benefits stakeholders derive from the peatlands. Further details on the methodology can be found in Annex 1. A table summarising the stakeholder interviews can be found in Annex 2.

Indigenous Peoples and local communities

Indigenous Peoples and local communities are key stakeholders, as they utilise the peatlands. However, we found little relevant information from the available literature on how Indigenous Peoples and local communities benefit from the peatlands. We therefore visited two sites (village locations anonymised as Site 1 and Site 2, to allow communities to more freely express their views), selected based on differing nearby land uses, a national park (Site 1) and an internationally certified logging concession (Forest Stewardship Council, Site 2). At Site 1 there was one ethnic group, the Mboshi, a Bantu ethnic group. At Site 2 there were two ethnic groups, the Sangha-Sangha, a Bantu ethnic group, and the Mbendjele, termed an Indigenous People, based on their distinct language, culture and beliefs1. The Mbendjele differ from the Mboshi and Sangha-Sangha, as they are much more mobile, moving between villages, fishing camps and forest camps.

Across both sites, we surveyed 93 households and conducted participatory activities with 417 people. Household surveys gathered information on socioeconomic characteristics, land tenure rights; and livelihood activities such as agriculture, fishing, harvesting non-timber forest products, hunting, and livestock breeding. We gathered information on land use, customary governance, aspirations and expectations for the future and conservation preferences using participatory mapping, seasonal calendars, interviews, focus group discussions and guided forest walks.

All communities collectively used all of the nearby ecosystem types to access resources for their livelihoods, including rivers, terra firme forests, seasonally flooded forest, and peat swamp forest. Fishing is the principal livelihood activity in the study sites. River and peatland fishing together contribute on average 62% to 68% of household income across the communities studied.

All communities collectively used all of the nearby ecosystem types to access resources for their livelihoods, including rivers, terra firme forests, seasonally flooded forest, and peat swamp forest. However, fishing is the principal livelihood activity in both study sites. In Site 1 in the Cuvette department, 90% of households engage in fishing across all ecosystems, with 52% of households fishing in the peatlands. In Site 2 in the Sangha department, 98% of households engage in fishing across all ecosystems, with 90% fishing in the peatlands. In the peatlands, fishing practices vary with the seasons: there is dam fishing in the peat pools at the end of the dry season, and net and line fishing in the peatlands during the rainy seasons. At Site 1, river and peatland fishing together contribute 66% of household annual income, similar to Site 2, where they contribute to 68% of the Mbendjele and 62% of Sangha-Sangha household annual income.

Beyond fishing, all households reported that they sourced Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) from the peatlands in the past 12 months. These include food, including edible leaves and fruit, oil, palm wine, honey, mushrooms; medicinal plants; non-edible plants such as Marantacae used as a wrapper for foodstuffs; thatch for the roofs of houses; timber for oars and house-building; and fibre from Raphias palms which is used to make household goods such as beds, stools, baskets, fishing traps and fishing rods. Finally, the wider landscape, including the peat swamp forest and non-peat forest, has use beyond the material, as the forest is believed to be home to spirits of the ancestors. For example, fetishes are made from plants with mystical powers and are used by hunters to make hunting and fishing successful. This is particularly true for the Indigenous Mbendjele, who see themselves as ‘forest people’, and the forest plays an important role in spiritual, physical, emotional and social wellbeing (Hoyte, 2023). According to one Mbendjele woman we interviewed, “If we live it is thanks to the forest … We find our way of life there, our food, our strength.”

The estimated economic value of the goods sourced from all ecosystems for each community was $2,807 per household per year in Site 1, and $1,910 per household per year in Site 2 for the Sangha-Sangha and $1,983 for the Mbendjele. Of this, the peatlands and rivers contribute more than other ecosystems to household revenue (60% at Site 1, 47% at Site 2), due to the economic value of fishing. These values include agriculture, which is practised on terra firme land, not in the peatlands, but is typically a secondary activity, mainly producing the staple food, manioc. Our results clearly show that at Sites 1 and 2, these are peatland- and river-dependent communities.

Perhaps surprisingly, we found that the Indigenous Mbendjele source goods of a similar average economic value to the Sangha-Sangha local community, despite their lower social status. Nonetheless, there are some differences in resource use by the Indigenous Peoples. The Mbendjele earn less revenue from agriculture and more from gathering NFTPs, compared to the Sangha-Sangha community in the same site.

In both the study sites, the majority of peatland-dependent populations are living in poverty, if defined as an income less than $2.15 per day ($785 per year). We show that at Site 1, 83% of households live below the poverty threshold, while at Site 2, 64% of Sangha-Sangha and 90% Indigenous Mbendjele households live below the poverty threshold2. This is higher than the national average in the Republic of Congo of 47% (World Bank, 2024). In terms of extreme poverty, we estimated that at Site 1, 48% of households earn less than $1 per day, and at Site 2, 53% of Indigenous Mbendjele households, and 23% of Sangha-Sangha households earn less than $1 a day. While food, including protein, is typically abundant, we show that poverty is endemic in peatland-adjacent communities, and therefore that a modest income increase from the peatlands could lift many households out of poverty. Further details of our research with Indigenous Peoples and local communities can be found in Annex 3.

The key expectation for local communities and Indigenous people is to keep access to their customary lands. This expectation was at the forefront of discussions about protecting the peatlands. Communities also wanted improved access to essential services such as health and education, telecommunications, and transport.

Finally, we discussed the Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ expectations and aspirations. The key expectation for both groups is to keep access to their customary lands. This expectation was at the forefront of discussions about protecting the peatlands. At Site 1, some of the community’s customary lands had been classified as a National Park, so they were then not able to use those areas. At Site 2, some of the customary land of both the Indigenous Mbendjele and the Sangha-Sangha had been classified as a forestry concession, restricting their access. These restrictions were reported to us to have increased hardship, specifically because fishing in the National Park and the forestry concession was restricted. This experience then led to a widespread and strongly negative view of the introduction of any potential new protections for areas of peatland. It was viewed that peatland protection measures would result in restrictions on access to the peat swamp forest, and any further restrictions on fishing were feared because of the hunger and suffering they would bring.

In terms of aspirations, everyone interviewed wanted improved access to essential services such as health and education, telecommunications, and transport. They also wanted their role as guardians of the peatlands to be recognised and to receive benefits, through community development initiatives, as a form of remuneration for their role in preserving the peatlands and other ecosystems within their customary lands. The Indigenous Mbendjele we interviewed wanted to be equal partners in the management of forest resources, noting that they wanted to implement ‘rest periods’ for the forest, and establish ‘zones of zero extraction’, as they have done traditionally, to allow forest resources to recover.

The Government of the Republic of Congo

The government of the Republic of Congo has made a series of commitments to sustainably manage the peatlands. These include the Brazzaville Declaration, 2018, the Letter of Intent between CAFI and the government of the Republic of the Congo, and the Law on the Sustainable Management of the Environment (2023). We conducted a literature review and interviewed representatives of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, Ministry of Forest Economy, Ministry of the Environment, Sustainable Development and the Congo Basin (MEDBCC), The Minister of State, Minister of Land Use Planning, Infrastructure, and Road Maintenance (MATIER), and the Programme for Sustainable Land Use (PUDT), about these commitments and the expectations of these ministries going forward.

The Ministry of the Environment, Sustainable Development and the Congo Basin is responsible for the management of the peatlands. It collaborates with the Ministry of Forest Economy which is responsible for the sustainable management of the state-owned forest and protected areas. There are structures for the coordination of different stakeholders’ interests, such as the Sustainable Land Use Programme (PUDT) and the inter-ministerial committee of the Ministry for Regional Planning.

The government of the Republic of Congo has made a series of commitments to sustainably manage the peatlands. The Forest Law of 2020 stated that the government will take “necessary measures for the protection and sustainable management of peatlands”. The Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment prohibits mining, forestry, agropastoral and aquaculture activities, petrol, gas and hydroelectric developments in peatland zones.

Before the mapping of the peatlands in 2017, the wetlands were recognised for their importance, with much of the peatland region designated as a Ramsar site called the Grands Affluents. Ramsar designation includes a commitment to sustainable management (Miles et al., 2017). In 2018, following the mapping of the peatlands, the government of the Republic of Congo signed the UN-brokered Brazzaville Declaration. This pledged to keep the peatlands wet and develop strategies for sustainable development for the peatland region. In 2019, the government of the Republic of Congo and the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI) signed a Letter of Intent committing to “ensure the conservation and sustainable management of forests to meet the needs of future generations”, with a specific clause applying this to the peatlands (CAFI & the Republic of Congo, 2019). CAFI is funding the government and its partners to define a special status for the peatlands and implement a spatial planning process.

In 2020 the government took further action to protect the peatlands. The Forest Law of 2020 committed the government to take “necessary measures for the protection and sustainable management of peatlands” (Law No. 33-2020, Forest Code, 2020). Three years later, the government strengthened these commitments by prohibits mining, forestry, agropastoral and aquaculture activities, petrol, gas and hydroelectric developments in peatland zones, and prohibiting peat extraction for commercial use, in a new 2023 Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment of (Article 45, Law No. 33-2023). The 2023 Law also states that each peatlands zone will have a management plan for conservation and sustainable management to be defined by the ministries of the environment, forests, land affairs, scientific research and regional planning, with input from peatland-dependent communities (Article 46). The Law also stated that the management plan and the legal status of peatlands zones will be approved by decree by a council of ministers (Article 47).

There are two protected areas in the peatlands that the government co-manages. Firstly, Ntokou Pikounda National Park, of which approximately 300,000 hectares is peatlands, and is legally a national park. Secondly, Lac Télé Community Reserve, which contains approximately 350,000 of peatlands, and is legally a ‘nature reserve’, with explicit rights for local communities and Indigenous peoples to conduct their livelihood activities. Lac Télé Community Reserve is home to an estimated 20,000 people. There are plans for the Lac Télé Community Reserve to be extended, by 193,400 hectares to the southeast (known as the Batanga Zone) and 520,025 hectares to the west (known as the Bailly Zone), which is mostly peatlands and would more than double the amount of peatland protected by the community reserve.

According to our interviews, the government receives little income from the peatlands. Industrial concessions overlapping the peatlands are not being actively exploited in the peatlands, and so they provide negligible income in the form of tax revenue. There is no large-scale logging or mining or commercial fossil fuel production in the peatlands, and so no income from these activities. The government has a benefit sharing agreement with the World Bank for emission reductions payments in the Likouala and Sangha departments, including the peatlands. However, no payments have been made to date. While there is little income from the peatlands, the Republic of Congo government receives attention on the international stage for its past and current stewardship of its tropical forests and the peatlands.

In terms of expectations and aspirations, government interviewees stated that their expectation is that their stewardship of this ecosystem must be recognised with financial payments. There is a hope that the international community will fund the long-term sustainable management of the peatlands. Mrs Arlette Soudan-Nonault, Minister of the Environment, Sustainable Development and the Congo Basin said to us that protecting the peatlands of the Republic of Congo is a priority, and that environmental objectives and human development go hand in hand, given the local population’s knowledge of how to live in harmony with the peatland ecosystem. The aspiration to protect the peatlands has been repeatedly made by the government of the Republic of Congo.

In interviews, government officials stated that their expectation is to generate state revenue from the protection of the peatlands. An official interviewed said, “Compensation will guarantee sustainable protection of peatlands.”

In interviews, government officials stated that their expectation is to generate state revenue from the protection of the peatlands. An official interviewed said, “Compensation will guarantee sustainable protection of peatlands” (Vidalie, A., 12 April 2024). Given the global importance of the peatlands, ministries are looking to international donors, companies and international organisations to create financial mechanisms for peatlands protection. Additionally, eco-tourism was cited by officials as an aspiration as a source of revenue. However, visitor numbers to established protected areas such as Ozdala-Kokoua National Park and Nouabli Ndoki National Park are low, and the peatlands would pose additional logistical challenges (Doumenge et al., 2021; IUCN, no date).

The need for government revenue is also the motivation for activities that would damage the peatlands, notably oil exploration and extraction. Additionally, some national development plans could severely impact the peatlands. The Ministry of Energy and Hydrology informed us of a plan to build a 30-Megawatt hydroelectric plant near Enyelle on the Ibenga River and Motaba River in the peatland region, for which an environmental impact study was underway in 2024. Also, a new road is planned to link Epena and Mboua in the Likouala department (MATIER, 2024), which could negatively affect the peatlands by changing drainage patterns, unless it is built carefully. The impact on the peatlands will need to be assessed before each infrastructure project plan to ensure it is compatible with the existing commitments to protect the peatlands.

Further details on government interests in the peatlands can be found in Annex 4.

The private sector

We conducted a literature review on private sector involvement in the peatlands. We also interviewed the logging company CIB-Olam, government representatives at relevant ministries, and civil society organisations active in forest monitoring and forest governance.

Forestry

There are eleven logging concessions overlapping the peatlands of the central Cuvette area in northern Congo (Global Forest Watch, 2025a). Logging in these areas is unlikely, as the Environment Law of 2023 prohibits industrial forestry in the peatlands. In addition, swamp forest has rarely been logged in the past, because the swampy conditions make selective logging difficult and expensive, and commercially valuable species of sufficient size are rare in the peatlands (République du Congo, 2020). Deforestation is exceptionally low in the peatlands (Jenkins et al., 2025).

In an interview, CIB-Olam said that they have no interest in exploiting timber in the peatlands, for environmental reasons, as well as because of the logistical constraints of doing so (Istace, V., 8 May 2024). Our analysis of tree cover loss data in the peatlands areas of the eleven concessions shows very low levels of forest loss (Global Forest Watch, 2025a). Four of the concessions with significant areas of peatlands are independently certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), whose guidelines exclude swamp forest from exploitation, suggesting the peatlands will not be logged (ATIBT, 2019). The non-FSC certified concessions present an increased risk of unsustainable practices, as even if logging does not take place in the peatlands, logging activities near the peatlands can indirectly affect peat, as new roads can alter the hydrology of large areas if they act as a barrier to water.

We estimate that there are negligible economic benefits of the peatlands for the forestry sector, because logging is prohibited by law. In terms of aspirations and expectations, companies want income from these areas. One potential future income stream being explored by forestry companies is from carbon credits. However, given the lack of historical deforestation or forest degradation in the peatlands and the prohibition on logging in peatlands, there is no clear ‘additionality’, suggesting carbon offsets for avoided emissions are unlikely to be available for the peatlands. Other sources of ecosystem service payments would be more suitable. Generating revenue streams from areas of peatland under commercial concessions is a challenge.

Oil

The possibility of commercially exploitable oil reserves beneath the peatlands poses a threat to the peatlands. The Congolese government has given permission to licence eight large oil blocks covering 4.67 million hectares of peatland (Ministère des Hydrocarbures, 2022). There is limited evidence of the existence of oil in commercially viable quantities in the peatland region. In 2019, Société Africaine de Recherche Pétrolière et Distribution (SARPD) Oil announced the discovery of oil from a single well in the Ngoki concession, which is in the peatlands. Based on this well and limited seismic data, they estimated future production at 983,000 barrels per day, nearly three times Congo’s daily production in 2019 of 350,000 barrels per day from offshore sources (AfricaNews, 2019; Les Echos, 2019). These estimates were met with high scepticism (Charpentier, 2019; Global Witness, 2020). To our knowledge, there has been no further drilling since 2019. This concession, now known as Ngoki II, is covered by a production sharing agreement, signed in April 2024 between the state oil company (SNPC) and SARDP (ADIAC, 2024). There are plans for seismic lines and two further wells.

The possibility of commercially exploitable oil reserves beneath the peatlands poses a threat to the peatlands. The Congolese government has given permission to licence eight large oil blocks covering 4.67 million hectares of peatland.

In contrast to this, some oil majors (Total, Eni) made early deals to explore for oil in the peatlands, but later withdrew citing “enormous difficulties in their development” (Ministry of Hydrocarbons, 2022). Furthermore, an academic review of past exploration in the region, including reanalyses of exploration well data from the colonial era, yielded no evidence of oil (Delvaux & Fernandez-Alonso, 2015). Apparent ‘oil seeps’ at the surface, noted by local people, suggest oil is present in the region, but scientific analysis of the material found at the surface show that these are not oil deposits, but are the result of local pollution events (Delvaux & Fernandez-Alonso, 2015). Old data, seemingly forgotten, is not consistent with the potential for large-scale oil discoveries. Thus, oil may not exist in commercially viable quantities.

Oil exploration, should it occur, would damage the peatlands via opening seismic lines which will likely expose the peatlands to increasing hunting pressure, and the more open forest canopy resulting from the seismic lines would increase the drying of the peatland in the dry season, resulting in new additional carbon emissions. If commercial production occurred, this would damage the peatlands via pollution from toxic ‘wastewater’ a co-byproduct of oil extraction, negatively impacting human and wildlife health. The influx of workers, would likely lead to increases in forest resource use, especially hunting and fishing. These impacts are well documented following oil exploration and production in peatlands in the Peruvian Amazon (Lawson et al., 2022; Lewis et al., 2022). Nonetheless, the government continues to encourage investment in exploration, but little on the ground exploration is currently under way, and there is currently no oil production from the peatlands area.

Mining

According to the Ministry for Regional Planning, Infrastructure and Road Maintenance (MATIER), there is no active mining in the peatlands in the Republic of Congo (Mabika Oufoura U., 10 May 2024). Some mining concessions are known to overlap with the peatlands: maps show four diamond mining concessions, one in Cuvette department, one in in Sangha department, and two in Likouala, that each overlap with the peatlands (Global Forest Watch, 2025b; MATIER, 2024; Rainforest Foundation, UK, 2020). The limited evidence available suggests these concessions are not active, consistent with the account given on the matter from MATIER.

Industrial Agriculture

There is no large-scale agriculture in the peatlands. Agropastoral and aquaculture activities are banned in the peatlands under the 2023 Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment (Article 45, Law No. 33-2023). There is also a prohibition on the conversion of areas of forest >5 ha to agriculture (Order N°9450/MAEP/MAFDPRP). The threat of large-scale oil palm plantations on the peatlands, a major peatlands land use change in Southeast Asia, is therefore unlikely in the Republic of Congo. Furthermore, an assessment of the potential for oil palm plantations in the Congo Basin shows that the peatlands are not very suitable for palm oil production (Feintrenie et al., 2016).

Historically, one large oil palm concession, the Atama concession, was granted that overlaps the peatlands. This was granted in 2011 and was suspended in 2017, with no oil palm ever being planted (Earthsight, 2018; Orozco & Salber, 2019). In terms of aspirations, the palm oil sector is focusing on national expansion on non-flooded lands, and not the peatlands, due to the illegality of conversion of areas >5,000 ha of peatland for agriculture, alongside much lower costs for expansion in non-flooded land.

Further details on the private sector can be found in Annex 4.

Civil society organisations and international donors

Civil society organisations and international donors (global north countries and philanthropic organisations) are also important stakeholders. Their interests include forest governance, human rights, sustainable development, wildlife protection, climate change mitigation and adaptation that are directly related to the peatlands and peatland-dependent communities. Their focus, depending on the organisation, differs in terms of the primary goal of their expected impact, spanning from the local to national to regional to global.

Most directly, wildlife conservation NGOs are co-managing large areas of peatlands included in protected areas, in partnership with the Ministry of Forest Economy. Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) co-manages Lac Télé Community Reserve and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) co-manages Ntokou Pikounda National Park, in partnership with the Congolese Agency for Wildlife and Protected Areas.

Donor countries provide funding for the protection of the peatlands through bilateral programmes and the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI). CAFI is a coalition of donors from Belgium, the European Union, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the Republic of Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States, that have established an $892 million Trust Fund, that supports direct investments in the region. CAFI is also a political negotiation platform to drive policy dialogue. Peatland-related CAFI-funded projects in Republic of Congo include preparing the definition of the legal status of the peatlands in the Republic of Congo (led by CIFOR, the Centre of International Forestry Research) and a programme of land-use planning (led by the Republic of Congo government).

Civil society organisations and international donors interests include forest governance, human rights, sustainable development, wildlife protection, climate change mitigation and adaptation. There is a broad consensus that the peatlands and the livelihoods of peatland dependent communities need to be protected. There is also a consensus that peatland dependent communities should have access to healthcare, education and other basic services.

Several bilateral programmes have funded peatland-related activities. The United States’ USAID funded the Central African Regional Programme for the Environment (CARPE) to protect tropical forests and forest-related livelihoods, including large areas of peatlands, for 30 years, until 2025. This programme is now closed. The Federal Government of Germany is financing a €15 million programme as part of their International Climate Initiative (IKI) aimed at enabling evidence-based decision making and good governance in the Congo Basin peatlands of both DRC and Republic of Congo, led by the United Nations Environment Programme. The UK government has funded approximately $5 million over 15 years, to university scientists to first ‘discover’ the peatlands and understand the extent, value and vulnerability of the peatlands. This CongoPeat research programme is co-led by Marien Ngouabi University, University of Kisangani, and the University of Leeds. Currently, the UK government is funding the Congo Basin Science Initiative, including some research on the peatlands. The Japanese government is also investing in peatland science, funding a $4 million programme to build a flux tower to measure the carbon balance of the peatlands at Lokolama, Equateur province, DRC, and an accompanying field research station.

In terms of expectations and aspirations, for civil society organisations and international donors, there is a broad consensus that the peatlands and the livelihoods of peatland dependent communities need to be protected. There is also a consensus that peatland dependent communities should have access to healthcare, education and other basic services. There is a broad expectation that the prohibition on industrial exploitation of the peatlands, in the 2023 Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment (No. 33-2023), will be enforced.

Beyond the broad overarching expectations and aspirations, the various organisations differ in their primary focus. For example, for the more community and human rights orientated civil society organisations and donors, there are aspirations that customary land tenure will be formalised so that peatland-dependent communities can have land tenure security, and that their role in the management of conservation areas will be formalised, as the primary consideration. This is envisioned to be implemented in a way that promotes wildlife conservation and protects the carbon stored in the peat. For more conservation and climate change orientated civil society organisations and donors, the protection of the peatlands to protect wildlife, wider biodiversity, and protect the climate is the primary consideration. This is envisioned to be implemented in a way that respects local people and their livelihoods.

For further details on Civil Society Organisations and International Donors, see Annex 5.

Stakeholder Summary

We found that there is widespread stakeholder engagement with the peatlands, including from the Republic of Congo government, who have made major progress on protecting the peatlands since they were mapped and brought to world attention in 2017. However, there is a competing desire to exploit the peatlands for oil, if commercially viable quantities can be found. The government stresses that the peatlands must generate income. We show that local communities are heavily reliant on the peatlands for sustenance and income, particularly for fishing. Some international NGOs co-manage significant areas of peatlands within the Lac Télé Community Reserve and the Ntokou Pikounda National Park, as do some private companies with forestry concessions that include peatland areas. Taken collectively, there is currently relatively little disturbance to the peatlands, and they appear mostly intact. Therefore, long-term protection is a viable possibility.

We found that there is significant common ground between stakeholders on the importance of protecting the peatlands for the ecosystem services they provide and the local livelihoods they support. Overall, there is a broad consensus that both the ecosystem services provided by the peatlands and the local sustainable livelihoods they support need to be protected. There is broad agreement that the peatlands should be maintained in their current largely intact state, with international funds being made available to achieve this.

Our study indicates that local and Indigenous communities fear that new formal protections for the peatlands will result in a loss of access to their customary lands in the peatlands, which would increase hardship in these communities. Our study shows that given how much local communities depend on the peatlands, imposing restrictions on local people’s access to the peatlands will likely increase poverty. Without care in explaining what protection entails this will lead to opposition to plans to protect the peatlands. The implication is that the route to protecting the peatlands and the livelihoods they sustain will require local communities to have continued access to their customary lands and have a formal role in managing the peatlands under any new legal status of the peatlands.

Options for the protection of the peatlands and peatland-dependent livelihoods

To assess the options for peatland protection we undertook an analysis of the legal framework in Republic of Congo that could allow peatland protection. We also conducted a literature review of potential protection options and consulted stakeholders in a workshop in Brazzaville in September 2024. This was attended by representatives, government ministries, the private sector, civil society, international donors, and local and Indigenous communities from Site 1 and Site 2 who we had previously engaged in this study.

The consultations with stakeholders revealed five key parts to any protection plan.

A continuation of the current inclusive process of consultation of local communities and Indigenous peoples. This will include Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) from Indigenous Peoples and local communities to any changes to the legal status, use, and management of the peatlands (Forest Code, 2020; Law on the Promotion and Protection of Indigenous Peoples, 2011). FPIC is needed to allay fears in local communities about losing access to customary lands. While FPIC is logically a first step, the co-creation of a plan to protect the peatlands is needed to present a concrete plan to local communities to consider agreeing to.

The current legal protections to avoid peatland drainage, deforestation or industrial uses need to be more fully implemented, monitored, and enforced. There was a concern that current protections need monitoring and enforcement for the long-term protection of the ecosystem.

Local communities that utilise the peatlands must continue to have access to the peatlands for their customary uses. There was strong opposition from communities that live adjacent to the peatlands and use the peatlands for their livelihoods to creating a ‘protected area’ to protect the peatlands because of fears of restrictions on access to the peatlands, particularly where fishing is conducted.

The management of the peatlands should be undertaken as a formal tripartite cooperation between government, Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and professional civil society organisations, to ensure that livelihood activities can take place alongside maintaining the integrity of the biodiversity and carbon in the peatlands.

Further finance will need to be sought to establish new protections, implement new management plans, and enable Indigenous Peoples and local communities and the Republic of Congo to develop sustainably.

One important framing question is whether there should be a single coherent plan for all the peatlands, a vast area of 5.5 million hectares. Or should the protection plan be focused on a series of more modestly sized management units, and possibly a more phased approach, one area or region at a time. These are not necessarily binary choices. It is possible to have a single coherent plan, and with a nested approach of smaller management units.

One key benefit of a single coherent plan is that this the approach of the government of the Republic of Congo, with the 2023 Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment recommending a special legal status for the peatlands, a peatlands policy developed across relevant ministries. Furthermore, acting at scale is likely to protect more peatland and more livelihoods. This is particularly the case as there is currently momentum to protect the peatlands and peatland-dependent livelihoods. We recommend continuing with the current approach of considering all the peatlands and their protection.

The key challenge of a single coherent plan is that being inclusive is more challenging when working at scale as there are many more stakeholders. Furthermore, if the process stalls for some reason, then there is the potential for the process of implementing peatland, livelihood protection and community development to stall across the entire region.

We recommend continuing the process within the 2023 Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment that considers all the peatlands and their protection within a single coherent plan, with a nested design to tackle the challenges of implementing the plan across a vast area of peatland.

Taking all this into account we recommend continuing the process of considering all the peatlands and their protection as a single coherent plan, with a nested design to tackle the challenges of implementing the plan across a vast area of peatland. For example, there could be a new legal designation, implemented by government decree that prohibits industrial development of the peatland, prohibits the conversion of the peat forests to other land cover types, and grants rights to local communities to engage in fishing and collecting nontimber forest products, in an area-based designation. A nested design would then also include different management plans in different areas of the peatlands, based on existing land uses (existing national parks, nature reserves, logging concessions, mining concessions), and desired future uses, which may have additional protections.

Conceptually, there are two broad approaches to the protection of the peatlands and peatland-dependent community livelihoods to make them operational. The first is to use the legislative framework relating to protected areas to protect the peatlands from drainage, land-cover change or industrial uses, and build-in legal recognition of local community and Indigenous Peoples’ customary rights to sustainably use the peatlands and their resources. The second is to use a legislative framework to protect local community and Indigenous Peoples’ customary rights and build-in protections for the peatlands to ensure they conserve biodiversity and carbon. The former utilises the norms of protections under the 2008 Law on Wildlife and Protected Areas, and latter are in line with protections under a framework known as ‘Other Effective Conservation Measures’ (OECMs).

While the two approaches have differing starting points and differing routes to achieving their outcomes, but the outcomes themselves – the protection of the peatland and livelihoods – are similar. Thus the choice of approach relates less to outcomes, but it may be the case that one route may be practically less challenging to accomplish. We discuss the two options in turn. Both options are compatible with implementing the 2023 Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment.

Protections under the Law on Wildlife and Protected Areas

The simplest approach to peatland protection is to use the law related to protected areas. An example of this approach is the Lac Télé Community Reserve, which was formally created as a ‘nature reserve’ using existing protected areas legislation. The decree forming the Lac Télé Community Reserve provides protection for the natural environment and explicitly does not prohibit fishing (Décret no 2001-220 portant création et organisation de la réserve communautaire de Lac Télé, 2001, Article 11). Lac Télé Community Reserve is 440,000 hectares is size, has 20,000 residents, protects 300,000 hectares of peatlands, and is co-managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Congolese Agency for Wildlife and Protected Areas (ACFAP), with input from local communities. This provides a working example of protecting the peatlands and peatland-dependent livelihoods.

The simplest approach to peatland protection is to use the law related to protected areas. Under this legislation nature reserves have a mandate of protecting landscapes of scientific or cultural value as well as conserving biodiversity (Article 12), with fishing and other livelihood activities being permitted if authorised by a competent authority (Article 13).

Formally, the 2008 Law on Wildlife and Protected Areas defines five types of protected area: national parks, nature reserves, wildlife reserve, wildlife sanctuaries and hunting areas. Nature reserves are the most appropriate to protecting the peatlands and local livelihoods. Specifically, a nature reserve is defined as “preserved with a view to promoting the free play of natural factors without any external intervention, except those required to maintain the natural state of the environment” (Article 5). Under legislation for creating a nature reserve, these reserves have a mandate of protecting landscapes of scientific or cultural value as well as conserving biodiversity (Article 12), with fishing and other livelihood activities being permitted if authorised by a competent authority (Article 13). The decree creating a protected area must be preceded by an environmental impact assessment and “consideration of the needs of the local populations” (Article 8).

National parks legislation is also theoretically possible, but it is less flexible, as the use of forest resources and other activities are prohibited unless they are either exempted in the act that creates the park or specified in the management plan (Article 12). Thus, the decree that created Ntokou Pikounda National Park, with 350,000 hectares of peatland, excludes local communities. There are no residents. Fishing, hunting, fuelwood collection and other activities are prohibited (Décret n° 2013 – 77 du 4 mars 2013 portant création du parc national de Ntokou-Pikounda dans les départements de la Sangha et de la Cuvette, Article 5). Local communities and Indigenous peoples are vehemently against National Parks, as they are excluded for accessing them. Designation as a nature reserve is better aligned with protection of the peatlands and livelihoods than designation as a National Park. The objectives of wildlife reserves, wildlife sanctuaries and hunting areas are too narrow for peatland and livelihood protection3.

If further consideration is given to the option of nature reserves with community use rights and community co-management, care will be needed in how the option is presented. Our stakeholder interviews found strong opposition from people living adjacent to the peatlands to the idea of creating a ‘protected area’ because of fears of restrictions on access to the peatlands, particularly where fishing is conducted. Local communities reported a strong fear of reduced access to fishing, and the resulting reduced income and food provision, leading to widespread food shortages and a deepening of poverty.

How peatland and livelihood protection is officially described, and how it is spoken about, is likely to be important in terms of community engagement and peoples’ fears of a loss of access to their customary lands. Care will be needed to note that legislation for a ‘community reserve’ (a nature reserve protecting landscapes of scientific or cultural value) is different from the legislation for a ‘national park’, with different rules, resulting in a very different situation ‘on the ground’. The example of the Lac Télé Community Reserve, with residents who have permission to fish, collect non-timber forest products, and hunt nonprotected species, may reduce fears in some local communities. Improved co-management with the local communities in Lac Télé Community Reserve would also assist in this regard. If this option is pursued, a process of engagement with peatland-dependent communities is recommended to facilitate a dialogue that leads to an expression of the preferred peatland protection pathway (Forest Peoples Programme, 2024).

The existing legislation for the creation of ‘nature reserves’ and the real-world working example of the Lac Télé Community Reserve that combines community access to resources and ecosystem protection, suggests that this is a viable route to protecting the peatlands and communities, for the long-term. However, local communities will need to be convinced that this option truly puts local communities at the heart of the co-management plan for an area, and is not merely a conservation project that allows local communities to continue fishing.

Protections using Other Effective Conservation Measures (OECMs)

The second approach is to focus on the local communities’ access to their customary resources and build in long-term protection for the peatlands and the ecosystem services that they provide. Areas that achieve long-term and effective biodiversity conservation outside of protected areas are termed ‘Other Effective area-based Conservation Measures’, or OECMs. These may offer an approach to protection with co-management and resource use by local communities. OECMs are designed to recognise areas where long-term and effective conservation of biodiversity is being achieved through management, even if this is not the primary goal of management. This applies in many areas of the peatlands where local community use and management is primarily for their livelihoods, sustenance, and cultural practices, but nevertheless are achieving significant biodiversity conservation outcomes. OECMs were agreed as a decision under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, and further developed by IUCN, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (Jonas et al., 2023, 2024). OECMs are geographically bounded and are governed by an agreed entity or group of entities. Conservation does not have to be a primary objective, but there must be a causal link between how the land is managed and the in-situ conservation of biodiversity. This option of protection puts local communities and Indigenous peoples in a central role in the emergence of new protections for their livelihoods and the peatlands. Much of the peatland area that is not already formally protected could fit these criteria, and these criteria fit most stakeholder expectations.

OECMs are designed to recognise areas where long-term and effective conservation of biodiversity is being achieved through management, even if this is not the primary goal of management. This applies in many areas of the peatlands where local community use and management is primarily for their livelihoods, sustenance, and cultural practices, but nevertheless is achieving significant biodiversity conservation outcomes.

There is no clear legislative framework in the Republic of Congo to create an OECM as a new category of land governance, as they are a relatively new globally agreed mechanism to mainstream conservation action. In this regard, the government has established a national working group to define the process for recognising OECMs (Note de service N° 1456/MEDDBC-CAB. 2024 du 30 juillet 2024 mettant en place le Groupe de Concertation Nationale pour l’identification et la reconnaissance des AMCEZ en République du Congo, 2024) and a draft protected areas law includes a definition of OECMs. The 2011 Law on the Protection of National and Cultural Heritage, could also provide a framework. In addition, the Republic of Congo is a signatory to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, and OECMs can form part of Republic of Congo’s contribution to the global agreement to protect 30% of the land and 30% of the ocean by 2030, under the Convention on Biological Diversity.

OECMs are attractive to many stakeholders as they recognise the use of the peatlands by Indigenous Peoples and local communities, increase protection of the peatlands and its biodiversity via monitoring and adaptive management, and can be co-managed by the government, Indigenous Peoples and local communities and civil society organisations. However, one challenge in terms of using an OECM to protect the peatlands is that OECMs are relatively new, so few are familiar with this approach. This could mean that stakeholder and funder buy-in may be harder to achieve. By contrast, the newness and flexibility of OECMs may also be an advantage in that OECMs could be adapted more precisely to the peatland context in the Republic of Congo. Overall, the outcomes following the designation of an OECM, with its protections for the peatlands and local community and Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods, is not dissimilar from the outcomes that would be achieved using the protected area legislative framework to create nature reserves with conditions to guarantee local community customary use access. The outcome of both approaches is similar as they are designed to meet stakeholders’ expectations. Both approaches are also consistent with the 2023 Environment Law’s proposal of a special legal status of the peatlands.

Other Approaches to Peatland Protection

There are a number of other less promising approaches, that we briefly note, collective land title, Community forests, and Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs).

Collective land title

Collective land title is the acquisition of title deeds by a group that has collective land rights, often Indigenous Peoples (UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2018). Congo’s 2011 Indigenous Law recognises that Indigenous Peoples have collective land rights, providing a foundation for the acquisition of land title (Law No. 5-2011, Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). To our knowledge there are no cases of Indigenous Peoples acquiring collective land title, but some Indigenous Peoples are part way through the process of acquiring title to their customary land in Peke near Ouesso (personal communication, Kodja, E., 6 May 2024; Agnimbat Emeka, M., 5 October, 2024). One clear limitation of using Indigenous Peoples’ land rights to protect the peatlands and peatland-dependent livelihoods is that these laws do not apply to local communities from other ethnic groups. Yet, if collective titles could be agreed for Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the peatlands, it has been shown that land held in collective title often leads to both long-term planning and long-term environmental benefits (Tseng et al., 2021). During our research, some community members observed that acquiring collective land title could empower communities to defend their land from potentially damaging classifications of areas of peatlands as commercial concessions. By contrast, other community members feared that land title could be acquired by individuals or powerful groups to the detriment of others. A lack of formal agreement to co-management with stakeholders beyond local communities would likely limit the appeal of collective tenure with some wildlife and biodiversity-oriented stakeholders and funders.

Community forests

In central Africa, legally acknowledged community management of forest is increasingly widespread, typically with income generation from selective logging. Conservation objectives are usually subject to a minimum legal requirement for community forests. In the Republic of Congo the 2020 Forest Code refers to ‘community development areas’ within logging concessions and separately ‘community forests’. Community development areas have been granted, although none have been granted in peat swamp forests, and community forests that are envisioned as outside of logging concessions have not been granted to date. Overall, this route to peatland protection is unlikely in the peat swamp forests, due to a lack of commercially viable timber, and the significant challenge of carrying out these activities in the peatlands in an ecologically sustainable manner. Therefore, this route to peatland protection is unlikely to occur at scale, and unlikely to be attractive to many stakeholders.

Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs)

Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) are areas that are managed and protected from major human-induced environmental change by Indigenous Peoples and local communities, where customary tenure is demarcated and the area is managed sustainably (ICCA Registry, 2024). ICCAs differ compared to the options for peatland protection discussed above, as ICCAs are self-declared by communities, rather than the state. A community can self-declare an ICCA if they, (i) have a “close and deep connection” with the land, (ii) manage their land through a functioning governance institution, and (iii) contribute “overall positively” to the conservation of nature as well as community wellbeing (ICCA Registry, 2024). The community reports their declaration of an area of land as an ICCA, after which there is a review process to confirm that it meets the ICCA rules (Sajeva et al., 2019; UNEP-WCMC, 2020). Globally, the number of ICCAs, also known as Territories of Life has been increasing, with many in Africa. However, to date there are none in Republic of Congo (Zanjani et al., 2023). Given that ICCAs are self-declared, the protections given to the peatlands and livelihoods are weak, meaning they would not meet most stakeholders’ desires for peatland protection. However, ICCAs are often a step towards later recognition by local or national authorities. Thus, ICCAs may be useful in enabling Indigenous Peoples and local communities to move forwards rapidly towards asserting their customary rights through self-declaration while the government legislates to formally protect the peatlands and local community rights to sustainably use the peatlands. ICCAs are likely to be complementary to other approaches.

Linking to UN Protection Initiatives

Another option in protecting the peatlands and the livelihoods the peatlands support is to link protection measures to either (i) the UN Ramsar Wetlands Convention, under which most of the peatlands in Republic of Congo are included, (ii) the UNESCO Biosphere Community Reserve programme, or (iii) the UNESCO World Heritage Site programme. We briefly discuss each in turn.

RAMSAR Wetlands Convention

The Grand Affluents UN Ramsar Convention designation covers much of the Republic of Congo peatlands. The Grand Affluents is formally recognised under the Convention as a wetland of international importance for biodiversity conservation and for supporting human life. The wetland is subject to the wise-use principles outlined in the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, in particular that local and national actions maintain the ecological characteristics of wetlands. The Grand Affluents area, or part of it, could therefore be built-upon to become either a Community Reserve or an OECM, described above. This approach would likely meet the needs of many of the stakeholders, including regarding access for Indigenous Peoples and local communities to fishing and other resources used in local livelihoods alongside in situ biodiversity protection.

UNESCO Biosphere Community Reserve

The peatlands could also be recognised as a UNESCO Biosphere Community Reserve. These are nationally nominated areas that are awarded a special status because they integrate the conservation of nature with sustainable human development and community involvement.

The nomination criteria are a good summary of what most peatlands stakeholders desire. UNESCO Biosphere Community Reserves are zoned into core areas (strictly protected), buffer zones (for activities aligned with sound ecological practices) and a transition area (for sustainable livelihoods). The benefit of zoning is that different stakeholders can be assured that their expectations are taken into account, as the core areas have high biodiversity protection, whereas the buffer zones ensure peatland-dependent livelihoods can continue (Barraclough & Maren, 2022; UNESCO, 2022). One important benefit of a UNESCO designation is adherence to known and globally recognised standards, which is likely to be attractive to some stakeholders and some funders. Indeed, UNESCO Biosphere Reserves are sometimes described as “donor darlings” because of their capacity to attract funding. In the peatlands context the core areas would likely be only in areas far from peatland access points and be a small fraction of the overall area. Any proposed strictly protected areas within customary lands would require discussion and FPIC. Given the zoning, UNESCO Biosphere Community Reserve incorporate elements of both nature reserves (Community Reserves) and OECMs.

UNESCO Biosphere Reserves are areas that integrate the conservation of nature with sustainable human development and community involvement. UNESCO Biosphere Reserves are sometimes described as “donor darlings” because of their capacity to attract funding.

In the Republic of Congo there is one UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Dimonika Biosphere Reserve, about 50 km from the Atlantic Coast. Odzala-Kokoua National Park was a Biosphere Reserve from 1977 to 2001 prior to its designation as a National Park (in 2023 it was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List). There are other successful UNESCO Biosphere Reserves in the central African rainforest region: the Dja Reserve in Cameroon and the Yangambi Biosphere Reserve in DRC. Legally, establishing a UNESCO Biosphere Community Reserve could use the Law on Wildlife and Protected Areas, as the core and buffer zones could be classed as nature reserves, with core areas having stricter protection.

UNESCO World Heritage Site

The peatlands could be recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage. A UNESCO World Heritage Site is a cultural or natural landmark of Outstanding Universal Value recognised by UNESCO for its global significance to humanity. All or part of the peatlands could be nominated by the Republic of Congo government, if they meet at least one of the ten criteria for listing that cover cultural and natural values. The peatlands likely meet criteria on both the cultural dimension (to be an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement, land-use, or sea-use which is representative of a culture (or cultures), or human interaction with the environment) and the natural dimension (to contain the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation). Critically, a nominated site must also show that the components have an adequate system of protection and management to ensure its conservation for future generations. These are all desires of many peatland stakeholders. Listing as a World Heritage site is often associated with increased in tourism and economic benefits.

For further information on the legal framework relating to the peatlands, see Annex 6.

A Protection Pathway for the Peatlands and Peatland- dependent Livelihoods

The government of the Republic of Congo has made significant advances in protecting the peatlands since they were mapped and brought to world attention. Specifically, the Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment (2023) covers peatland protection. This Law names the peatlands as a nature reserve and prohibits industrial exploitation of the peatlands (Article 45). Furthermore, the law states that each peatlands zone will have a management plan for conservation and sustainable development to be defined by the ministries of the environment, forests, land affairs, scientific research and regional planning, with local communities being involved in the development and implementation of the management plan (Article 46). It commits the government to passing a decree approved by a council of ministers to give the peatlands a legal status (Article 47).

Under the Republic of Congo legal system, laws are adopted by Parliament, such as the Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment 2023, but their operationalisation and resulting enforcement depends on the issuance of an implementing decree or decrees (executive orders with legally binding consequences). An implementing decree or decrees will need to be drafted and passed to build upon the Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment 2023 to protect the peatlands and customary uses of the peatlands by peatlands-dependent communities.

In outline, if the approach to peatland protection continues as a single coherent plan, as envisaged under the Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment 2023, and taking into account the stakeholder preferences reported, we propose a that the government passes a decree to implement and monitor core baseline protections for the peatlands and peatland-dependent livelihoods.

If peatland protection continues as a single coherent plan, as envisaged under the Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment 2023, we propose a that the government passes a decree to implement and monitor core baseline protections for the peatlands and peatland-dependent livelihoods.

Following this we suggest an operational phase, based on identified area-based management units that take into account current land uses, stakeholder desires for co-management, community development plans, and other activities, which would require further implementing decrees. This approach allows for the peatlands to be protected and progress to be maintained. It offers a nested design where area-based management is co-designed and tailored to the specific locations within the peatland region, all within existing Republic of Congo legal frameworks and current policies.

We suggest that the initial decree should operationalise the prohibition on the industrial uses of the peatlands, as included in the 2023 Law on Sustainable Management of the Environment. In our view it should also include an explicit binding duty to maintain the hydrology and vegetation of the peatlands, by prohibiting drainage of the peatlands and deforestation, as originally noted in the Brazzaville Declaration. Keeping the peatlands wet and forested will naturally result in biodiversity protection, including the fish that local communities rely on. Additionally, given the clear and consistent stakeholder feedback on the importance of local community and Indigenous Peoples’ continued use and management of the peatland, we suggest that the implementing decree includes a binding guarantee of the rights of the people with customary use of the peatlands to fish, collect non-timber forest products, and hunt non-protected species in a sustainable manner, alongside the right to continue rituals and other cultural practices in the peatlands.

The final part of the initial implementing decree should be to provide the enabling conditions to ensure that appropriate area-based management plans, community development plans and other activities that have been identified by the stakeholders can be implemented in a timely manner. This builds on Article 46 of the 2023 Law which states that each peatland zone will have a management plan for conservation and sustainable development with local communities being involved in the development and implementation of the management plan. We suggest that the initial implementing decree should include recognition that management should be tripartite between the government, local communities and Indigenous peoples with customary land use, and other relevant civil society organisations.

We suggest that the initial decree should operationalise the prohibition on the industrial uses of the peatlands, including a binding duty to maintain the hydrology and vegetation of the peatlands, and a binding guarantee of the rights of the people with customary use of the peatlands to fish, collect non-timber forest products, and hunt non-protected species in a sustainable manner.

Once a draft decree is written it will need to be translated into messages that are clear to stakeholders including the peatland-adjacent communities. These are needed to consult with local communities and Indigenous peoples to assess whether the decree is acceptable, in a process of Free Prior Informed Consent. The Network of Indigenous and Local Peoples for the Management of Central African Ecosystems (REPALEAC), the Forest Peoples Programme, and Rainforest Foundation UK have each developed methodologies for assessing conservation pathways and sustainable management of resources with local communities and Indigenous peoples and could manage the consultation and the FPIC process. These organisations could be engaged to design an appropriate FPIC process that maintains progress on protecting the peatlands, as the decree is formalising their rights. Once broad agreement is attained from stakeholders on the decree, and the decree is passed, this would formally protect the peatlands and protect local communities’ sustainable use of the peatlands.

By using our proposed nested approach, within the framework of the 2023 Law, the implementing decree protects the peatlands and formally gives rights to local communities’ traditional resource use. This is possible to be concluded without either new formal management plans, detailed community development plans or independent monitoring as the peatlands are being broadly utilised sustainably at present. These can follow in the second phase, to be developed within the legal framework of the 2023 Law and its initial implementing decree. The ambition of the management and sustainable development plans, particularly the community development plans, which are necessarily long-term and open-ended, will critically depend on the funds available.

To draft and adopt an implementing decree to protect the peatlands requires preparatory steps by the Republic of Congo government. In our view, there are some pieces of work to be completed that could be externally funded and contracted to relevant experts to provide necessary information to the government and other stakeholders, to maintain momentum. These are:

A map of the peatlands conforming to the legal definition of the peatlands agreed to by the government of the Republic of Congo.

The mapping of administrative boundaries, hydrological catchment areas, community uses, and current land uses, to align them with peatland protection. This information is needed to define the outer boundary of the area that the implementing decree will apply to, and the initial stage of the mapping of area-based management units for the peatlands.

A process of community consultation on an implementing decree as part of a process of Free Prior Informed Consent.

The mapping of the peatlands is required as baseline information necessary to protect the peatlands, as the decree will be area-based, that is it will apply to a specific area. Once a legal definition of the peatlands is agreed by the government and key stakeholders, the CongoPeat network, led by University of Leeds and Marien Ngouabi University have funds to map the peatlands to a legal definition, to improve on the existing mapping that is currently guiding the government’s progress on peatland protection (Crezee et al., 2022). If the legal definition of the peatland is similar to the scientific definition used for past maps (a wetland with seasonal waterlogging and an organic matter depth of at least 30 cm composed of at least 65% Organic Matter), then the mapped area will be similar, and further planning could occur on this basis. The definition and the resulting peatlands map will need to be deemed credible by international scientists and others to enable international funding to flow.

The boundaries of the peatlands, established according to a legal definition of a peatland will not fully align with administrative boundaries, hydrological boundaries, and local community use of the peatlands. Therefore, the peatlands need to be mapped alongside these and other existing land uses (such as logging concessions or national parks) to delineate where the implementing decree to protect the peatlands and community customary use will apply. Additionally, the government may want to exclude some areas of peatland from protection under the implementing decree. Furthermore, it is essential to know the area that the implementing decree will apply to in order to know which communities are inside the area to be covered by the decree, and therefore which communities need to be consulted as part of a process of Free Prior Informed Consent. Similarly, administrative boundaries need to be considered as these will likely be the most important boundaries for monitoring compliance with the decree. Compiling area-based information and maps on each of these – and aligning them – will be needed by the government, as they will need to decide on the outer boundaries of the area covered by the implementing decree.

A map of the peatlands to a legal definition of peatlands is required, as a decree will apply to a specific area. But, the boundaries of the peatlands will not align with administrative boundaries, hydrological boundaries, national management plans (national parks, logging concessions), and local community use of the peatlands. Mapping these alongside the peatlands is essential.